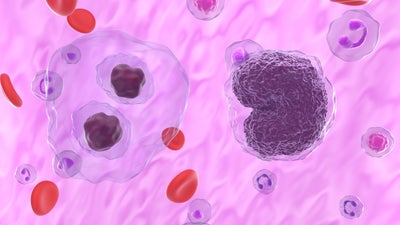

Myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorders

Overview

Myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorders are a group of conditions affecting different types of blood cells.

These are rare conditions, most often diagnosed in people over 65 and more common in men than women. In the past, they were often considered separate from cancer. However, modern medical understanding has shifted. Today, these conditions are generally classified as types of blood cancers or pre-cancers, because they involve uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in the bone marrow.

Learn more: Blood cancer

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

In MDS, the bone marrow does not produce blood cells as well as it should. It overproduces one or more types of abnormal blood cells, which don't function properly. These abnormal cells crowd out the normal blood cells, leading to a low production of healthy cells. Without treatment, certain types of MDS can progress to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

We do not know exactly what causes MDS, but it is likely to involve several factors working together. Some people have a gene change or mutation. Smoking and contact with a chemical called benzene may also be a factor. Younger people can develop MDS if they have had chemotherapy or radiotherapy to treat cancers.

Symptoms

Some people may not experience any symptom of MDS; it is diagnosed by chance during routine blood tests. Common symptoms include:

- feeling tired and appearing pale due to low red blood cells (anaemia)

- difficulty fighting off infections due to low white blood cells

- frequent bruising or bleeding, such as nosebleeds, due to low platelet count.

Treatment

The treatment you receive depends on several factors: the type of MDS you have, your test results, and your age and overall health. If you don't have any symptoms, your doctor may monitor your health and delay treatment until it's necessary.

If you experience symptoms, you may need transfusions to replenish your red blood cells and platelets. Additionally, blood cell growth factor injections may be given to increase low blood cell counts. Your doctor might recommend chemotherapy or a drug called lenalidomide to manage the MDS. If you're young and healthy enough, you may be offered a stem cell transplant using blood cells from a donor, known as an allogeneic transplant. This is the only potential cure for MDS, but it's a difficult procedure and is typically reserved for cases where there's a significant risk of the MDS developing into leukaemia.

Outlook

As a group of conditions, MDS can vary so much that it is not really helpful to look at overall statistics. It is best to ask your own specialist, who will have the relevant information on your case and treatment.

Doctors group MDS into different risk categories, depending on test results. People with mild MDS that is low risk can live with it for many years.

Myeloproliferative disorders

A myeloproliferative disorder means your bone marrow is making too many of one type of blood cell. There are four main types including, chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), polycythaemia vera (PV), essential thrombocytosis (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF).

Polycythaemia vera (PV)

With PV, your bone marrow produces too many red blood cells. You may also have an excess of white blood cells and platelets, which are cells that help the blood clot. Over time, the bone marrow can become dense with scar tissue (myelofibrosis), which may impair its ability to produce sufficient blood cells of any type. In advanced cases, PV can also transform into acute myeloid leukaemia.

Polycythaemia vera is rare but becomes more common with age. It is uncommon to diagnose this condition in individuals under 40, while it is most prevalent in people over 70. Additionally, it is slightly more prevalent in men.

The cause of PV is not well understood. Nearly everyone diagnosed has a particular gene mutation, but PV does not often run in families. You do not inherit the gene change; it happens after you have been born.

Symptoms

Some people do not have symptoms and are diagnosed with PV after a routine blood test. PV increases your risk of blood clots, and some people are diagnosed after experiencing a heart attack or stroke. If you have symptoms, they may include:

- other signs of a blood clot, such as a DVT (deep vein thrombosis)

- problems with bleeding in the past, such as a bleeding stomach ulcer or blood in your stool

- headaches, dizziness, or blurred vision caused by ‘thickened’ blood

- severe itching, which may start when your skin comes into contact with warm water

- redness, pain, or a burning sensation in fingers and toes

- a red complexion.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to reduce your risk of blood clots. The type of treatment depends on your risk level, which is affected by your age and whether you have had a blood clot in the past.

- Low or moderate risk of clots: your doctor will give you low-dose aspirin. You are also likely to have some blood removed, up to two or three times a week. This process is similar to giving blood, with a needle in your arm draining the blood into a bag.

- High risk of clots: you will receive the same treatment as those with low risk, but with the addition of medication to reduce the number of red cells. This often involves a chemotherapy tablet.

- Densely fibrosed bone marrow (myelofibrosis) or PV that has transformed into leukaemia: your doctor may suggest a stem cell transplant using cells from a donor, known as an allogeneic transplant. You can only undergo this treatment if you are young and fit enough, as it is challenging to endure.

Outlook

Polycythaemia vera (PV) is a long-term, slowly developing condition. On average, people with low-risk PV live for around 30 years after diagnosis. Even with high-risk PV, the average survival time is over 10 years.vvvv

Essential thrombocytosis (ET)

Essential thrombocytosis (ET), also known as primary or essential thrombocythemia, is a rare disease that can be diagnosed at any age. It is most common in people between the ages of 50 and 70, and it is more prevalent in women.

If you have ET, your bone marrow produces too many platelets, which are cells that help your blood clot. Over many years, fewer than one in 20 people with ET develop myelofibrosis, a condition where scar tissue forms in the bone marrow. This can lead to insufficient production of all types of blood cells. In advanced cases, ET can also transform into acute myeloid leukaemia.

The cause of ET is unknown. Almost everyone diagnosed has a specific gene mutation, but ET usually does not run in families. The gene mutation occurs after birth.

Symptoms

Up to half of those with ET do not experience any symptoms, and the condition is often discovered through routine blood tests. When symptoms do occur, they may include:

- headache, dizziness, or light-headedness

- blood clot-related issues, such as heart attack, stroke or deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- mottled skin, particularly on the legs

- burning pain and redness in the feet and hands

- increased risk of miscarriage.

Treatment

If you are asymptomatic you may not require treatment, but your doctor will monitor your condition with regular blood tests. To control symptoms, most people are prescribed low-dose aspirin.

In addition to low-dose aspirin, individuals over 60 or those with a history of blood clots may be treated with medication to reduce the number of platelets, usually in the form of a chemotherapy tablet. Your doctor may also recommend an anti-clotting drug, such as heparin or warfarin.

For severe cases with densely fibrosed bone marrow (myelofibrosis), your doctor might suggest a stem cell transplant using cells from a donor (an allogeneic transplant). If you are healthy enough, a donor stem cell transplant may also be recommended if ET has transformed into leukaemia.

Outlook

Most people with ET have a normal lifespan. Serious complications like myelofibrosis or leukaemia develop in only one or two out of 20 people at most.

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF)

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is a rare disease that usually affects people in middle to older age. The average age at diagnosis is around 65, and it is equally common in men and women.

In PMF, scar tissue forms in the bone marrow, which reduces its ability to make blood cells. This leads to low levels of white cells, red cells, and platelets. Eventually, the bone marrow may fail completely.

Symptoms

If you have PMF, you might experience:

- feeling very tired, weak, and short of breath due to low red blood cells (anaemia)

- fevers and night sweats

- weight loss

- loss of appetite or feeling full quickly because of an enlarged liver or spleen

- bone pain

- easy bruising or bleeding because of low platelets.

Treatment

Treatment for PMF depends on your symptoms and overall health.

- Monitoring: if you have no symptoms, your doctor may just monitor your health.

- Stem cell transplant: the only way to cure PMF is a stem cell transplant from a donor. This is considered if you have symptoms and are fit enough for the treatment.

- Medications: if you are not fit enough for a transplant, medications can help manage symptoms.

- Spleen treatment: If you have pain or discomfort in your abdomen, your doctor may suggest surgery to remove your spleen or radiation to shrink it.

Outlook

The outlook for people with PMF varies widely. On average, people live around five years after diagnosis. However, some people may live less than a year, while others can live up to 30 years. It's best to talk to your specialist for information about your specific case and treatment options.

A blood cancer or a blood disorder diagnosis can feel overwhelming, but you're not alone. Partnering with DKMS can help you share your story and amplify our combined efforts to expand the stem cell registry, so do reach out to us. Together, we can create more hope and opportunities for people living with blood cancer.

References

Myelodysplastic syndrome. Summary. BMJ Best Practice.

What is myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Research UK.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms and myelodysplastic syndrome. Myelodysplastic syndrome: approach to the patient. Oxford Medicine Online.

Tests and treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Treatment for myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Research UK.

Myelodysplastic syndrome. Treatment algorithm. BMJ Best Practice.

Polycythaemia vera. Epidemiology. BMJ Best Practice.

Polycythaemia vera. History and exam. BMJ Best Practice. Last reviewed February 2021.

Murata M, Suzuke R, Nishida T et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for post-essential thrombocythemia and post-polycythemia vera Myelofibrosism. Internal Medicine, 59(16), pp1947-56. Published August 2020.

Polycythaemia vera. Prognosis. BMJ Best Practice.

Essential thrombocytosis. Epidemiology. BMJ Best Practice.

Prognosis and treatment of essential thrombocythemia. Post-ET myelofibrosis. UpToDate.

Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of essential thrombocythemia. Pathogenesis. UpToDate.

Diagnosis and clinical manigestations of essential thrombocythemia. Clinical features. UpToDate.

Harrison CN, Bareford D, Butt N et al. Guideline for investigation and management of adults and children presenting with a thrombocytosis. Key recommendations: Post‐ET myelofibrosis (MF). British Journal of Haematology, 149(3), pp352-375.

Management of primary myelofibrosis. Management of higher-risk PMF. UpToDate.

Essential thrombocytosis. Prognosis. BMJ Best Practice.

Myelofibrosis. Summary. BMJ Best Practice.

Clinical manigestations and diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis. Clinical manifestations. Up to date. L

Myelofibrosis. Management: Approach. BMJ Best Practice.

Myelofibrosis. Prognosis. BMJ Best Practice.